When Adobe Photoshop first debuted, it looked like magic. The ability to seamlessly alter photos gave graphic designers a life-changing tool, but it wasn’t long before users started to use the product for more nefarious purposes. As recently as last year, for example, a photo of NFL player Michael Bennett of the Seattle Seahawks appearing to be holding a burning flag in the team’s locker room went viral, even though it had merely been Photoshopped.

By now, Photoshop (and “Photoshopping,” it’s adapted verb version) has become shorthand for speaking about any manipulated photo. The way the term has woven itself into our everyday language demonstrates how widespread our understanding that images can be easily digitally manipulated has become. People are often willing to point out and accept that a photo has been altered. (Though, as the Bennett photo demonstrates, there are still exceptions to the rule, and many who are still fooled.)

What happens when Photoshop (or programs like it) becomes so advanced that it’s nearly impossible to spot a fake? What if there wasn’t a way to easily point out that something had been doctored or substantially altered because only a minority of people knew the manipulation was even possible? This is the case with Adobe VoCo, a program that allows users to edit voices — and not just the pitch or speed, but also what someone has said. Beyond just rearranging words in a voice recording, Adobe VoCo can make a person “say” something they never said at all.

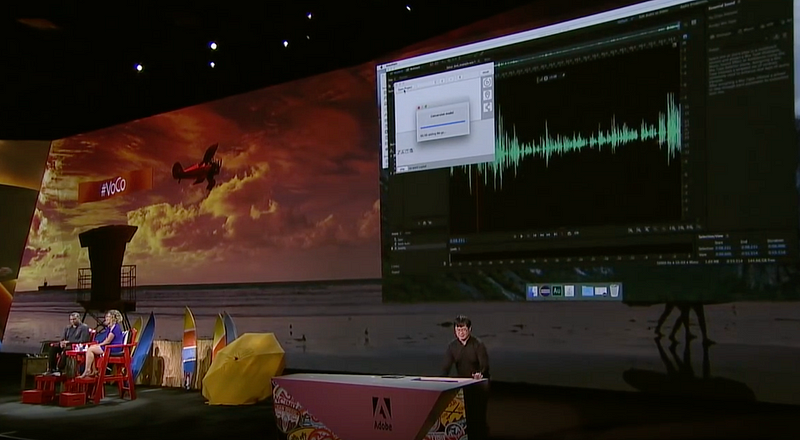

Image: Adobe Creative Cloud/YouTube

Demonstrated in late 2016, the program is billed as “Photoshop for voice,” and part of the demonstration showed how to alter a voice recording of Keegan-Michael Key, of Key & Peele fame. It seamlessly shifted the order of words within the recording, in addition to adding new words to it.

In a matter of minutes, “I kissed my dogs and my wife” became “I kissed Jordan three times.”

The quality of the alteration, unlike more rudimentary methods of manually splicing vocal recordings, can make it hard to catch. The recording was changed merely by uploading the clip into VoCo, which then displayed the words being said under the vocal recording. All the user has to do is move words around or type in additional ones.

Predictably, the audience met the demo with cheers and applause, while Jordan Peele, who was emceeing the event, jokingly declared, “You’re a demon!”

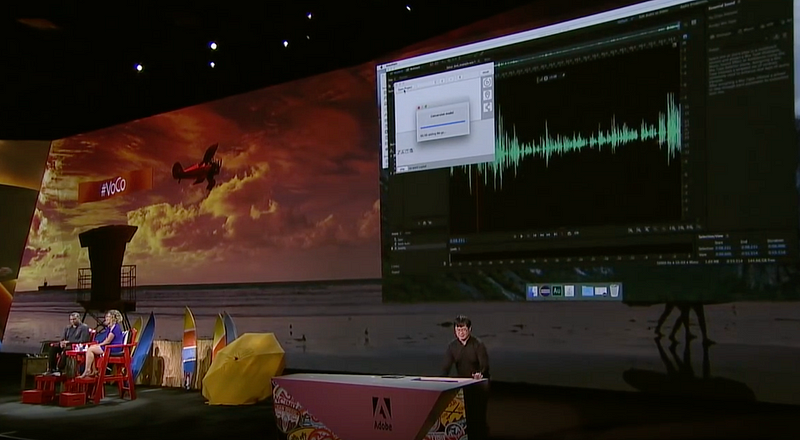

Image: Adobe Creative Cloud/YouTube

VoCo takes in large amounts of voice data and breaks it into the distinct sounds that make up spoken language, collectively known as phonemes, before creating a voice model of whoever is recorded. If a word isn’t already in the recording, then the program will use these phonemes to create it from scratch.

There are numerous uses for such technology, most obviously in podcasting, given their increasing popularity over the past decade. From 2008 to 2015, the number of podcasts on iTunes rose by 50,000; over the same time period, listeners increased from 9 percent of the American public to 17 percent, according to MarTech, a marketing research website. Audio editing is a tedious process that could likely be made much easier with a program like VoCo. Software like this would also make it easier for amateurs to get into podcasting without needing extensive production experience or training.

As with many content-manipulation technologies, over the initial applause and adulation loom questions about the way such tech could easily be used to cause harm and spread fake news.

“One of the main fears of this kind of technology, where you can augment audio, is really about how can that be used in war,” says Joan Donovan, the media manipulation and platform accountability lead at the Data and Society Research Institute, which examines the social and cultural issues arising from data-centric and automated technologies.

“You can imagine in the midst of a breaking news event something like this being used to pretend there is a leak, that someone is making a death threat against a public figure, or that so-and-so has called for an invasion. There are all kinds of ways that this technology, if people don’t readily know it’s available, could be weaponized against the public,” Donovan says.

Consider something like War of the Worlds, Orson Welles’ infamous radio broadcast from 1938, which was so convincing that it caused some to panic, believing that an alien invasion was not fiction but, in fact, breaking news. Imagine Adobe VoCo taking the voice of a nation’s president and having them announce something equally as alarming over the airwaves.

Unlike Photoshop, programs such as Adobe VoCo aren’t widely known, which makes people more susceptible to them. If you described Adobe VoCo to a friend, perhaps they might say they could imagine it, but would they know it already exists? And that it’s practically on the market?

These kind of voice alterations could allow anyone to improve upon classic phishing campaigns—say, requesting someone’s password while pretending to be a family member or a boss. If you wanted to create a widespread false-information operation, the software could be used to spread fake audio clips. Or it could be used simply to harass people. Journalists regularly receive threatening emails — what if those were phone calls or voicemails that appeared to be from friends or acquaintances? Some of our more secure institutions, such as banks, use voice verification as a part of their security. Imagine if Donald Trump claimed the damning audio of him bragging to Billy Bush about sexually assaulting women had been digitally altered?

Researchers like Donovan have put together the digital tools needed to go back and see when, where, and how certain images have been manipulated. But she characterizes it as a losing game, because they’ll always lag behind the most recent technology. Widespread tools for identifying falsified speech are the next hill to climb.

Some biometric security companies believe they’re ready for this wave of technology, however, as more companies (including Google’s DeepMind audio-mimicking system WaveNet) move into this security space.

“The technology is new, but its underlying principles have been understood for some time,” Steven Murdoch, a cybersecurity researcher from University College London, told the BBC. “Biometric companies say their products would not be tricked by this because the things they are looking for are not the same things that humans look for when identifying people. But the only way to find out is to test them, and it will be some time before we know the answer.”

Adobe also seems well aware of the risks involved. The company has not yet released a beta of VoCo for download, and as of late 2017, it was still testing and developing the program. At the initial demo, Adobe’s presenter explained potentially using audio watermarks, a unique electronic identifier embedded in a recording and often used to identify who has ownership of copyright, to demonstrate whether an audio clip had been edited.

By now, Photoshop (and “Photoshopping,” it’s adapted verb version) has become shorthand for speaking about any manipulated photo. The way the term has woven itself into our everyday language demonstrates how widespread our understanding that images can be easily digitally manipulated has become. People are often willing to point out and accept that a photo has been altered. (Though, as the Bennett photo demonstrates, there are still exceptions to the rule, and many who are still fooled.)

What happens when Photoshop (or programs like it) becomes so advanced that it’s nearly impossible to spot a fake? What if there wasn’t a way to easily point out that something had been doctored or substantially altered because only a minority of people knew the manipulation was even possible? This is the case with Adobe VoCo, a program that allows users to edit voices — and not just the pitch or speed, but also what someone has said. Beyond just rearranging words in a voice recording, Adobe VoCo can make a person “say” something they never said at all.

Image: Adobe Creative Cloud/YouTube

Demonstrated in late 2016, the program is billed as “Photoshop for voice,” and part of the demonstration showed how to alter a voice recording of Keegan-Michael Key, of Key & Peele fame. It seamlessly shifted the order of words within the recording, in addition to adding new words to it.

In a matter of minutes, “I kissed my dogs and my wife” became “I kissed Jordan three times.”

The quality of the alteration, unlike more rudimentary methods of manually splicing vocal recordings, can make it hard to catch. The recording was changed merely by uploading the clip into VoCo, which then displayed the words being said under the vocal recording. All the user has to do is move words around or type in additional ones.

Predictably, the audience met the demo with cheers and applause, while Jordan Peele, who was emceeing the event, jokingly declared, “You’re a demon!”

Image: Adobe Creative Cloud/YouTube

VoCo takes in large amounts of voice data and breaks it into the distinct sounds that make up spoken language, collectively known as phonemes, before creating a voice model of whoever is recorded. If a word isn’t already in the recording, then the program will use these phonemes to create it from scratch.

There are numerous uses for such technology, most obviously in podcasting, given their increasing popularity over the past decade. From 2008 to 2015, the number of podcasts on iTunes rose by 50,000; over the same time period, listeners increased from 9 percent of the American public to 17 percent, according to MarTech, a marketing research website. Audio editing is a tedious process that could likely be made much easier with a program like VoCo. Software like this would also make it easier for amateurs to get into podcasting without needing extensive production experience or training.

As with many content-manipulation technologies, over the initial applause and adulation loom questions about the way such tech could easily be used to cause harm and spread fake news.

“One of the main fears of this kind of technology, where you can augment audio, is really about how can that be used in war,” says Joan Donovan, the media manipulation and platform accountability lead at the Data and Society Research Institute, which examines the social and cultural issues arising from data-centric and automated technologies.

“You can imagine in the midst of a breaking news event something like this being used to pretend there is a leak, that someone is making a death threat against a public figure, or that so-and-so has called for an invasion. There are all kinds of ways that this technology, if people don’t readily know it’s available, could be weaponized against the public,” Donovan says.

Consider something like War of the Worlds, Orson Welles’ infamous radio broadcast from 1938, which was so convincing that it caused some to panic, believing that an alien invasion was not fiction but, in fact, breaking news. Imagine Adobe VoCo taking the voice of a nation’s president and having them announce something equally as alarming over the airwaves.

Unlike Photoshop, programs such as Adobe VoCo aren’t widely known, which makes people more susceptible to them. If you described Adobe VoCo to a friend, perhaps they might say they could imagine it, but would they know it already exists? And that it’s practically on the market?

These kind of voice alterations could allow anyone to improve upon classic phishing campaigns—say, requesting someone’s password while pretending to be a family member or a boss. If you wanted to create a widespread false-information operation, the software could be used to spread fake audio clips. Or it could be used simply to harass people. Journalists regularly receive threatening emails — what if those were phone calls or voicemails that appeared to be from friends or acquaintances? Some of our more secure institutions, such as banks, use voice verification as a part of their security. Imagine if Donald Trump claimed the damning audio of him bragging to Billy Bush about sexually assaulting women had been digitally altered?

Researchers like Donovan have put together the digital tools needed to go back and see when, where, and how certain images have been manipulated. But she characterizes it as a losing game, because they’ll always lag behind the most recent technology. Widespread tools for identifying falsified speech are the next hill to climb.

Some biometric security companies believe they’re ready for this wave of technology, however, as more companies (including Google’s DeepMind audio-mimicking system WaveNet) move into this security space.

“The technology is new, but its underlying principles have been understood for some time,” Steven Murdoch, a cybersecurity researcher from University College London, told the BBC. “Biometric companies say their products would not be tricked by this because the things they are looking for are not the same things that humans look for when identifying people. But the only way to find out is to test them, and it will be some time before we know the answer.”

Adobe also seems well aware of the risks involved. The company has not yet released a beta of VoCo for download, and as of late 2017, it was still testing and developing the program. At the initial demo, Adobe’s presenter explained potentially using audio watermarks, a unique electronic identifier embedded in a recording and often used to identify who has ownership of copyright, to demonstrate whether an audio clip had been edited.

No comments:

Post a Comment