If you’re like most people in America, you use a text editor nearly every day. Whether it’s your basic Apple Notes, or something more advanced like Google Docs, Microsoft Word or Medium, our text editors allow us to record and render our important thoughts and information, enabling us to tell stories in the most engaging ways.

But you might not have ever thought about how those text editors work under the hood. Every time you press a key, hundreds of lines of code may be executing to render your desired character on the page. Actions that seem small — such as dragging a selection over a few words of text or turning text into a heading — actually trigger lots of changes in the system underlying the program.

While you may not think about the code powering these complicated text-editing maneuvers, my team here at The New York Times thinks about it constantly. Our primary task is to create an ultra-customized story editor for the newsroom. Beyond the basics of being able to type and render content, this new story editor needs to combine the advanced features of Google Docs with the intuitive design focus of Medium, then add lots of features unique to the newsroom’s workflow.

For a number of years, The Times’s newsroom has used a legacy homegrown text editor that hasn’t quite served its many needs. While our older editor is intensely tailored to the newsroom’s production workflow, its UI leaves much to be desired: It heavily compartmentalizes that workflow, separating different parts of a story (e.g. text, photos, social media and copy-editing) into completely different parts of the app. Producing an article in this older editor therefore requires navigating through a lengthy series of unintuitive and visually unappealing tabs.

In addition to promoting a fragmented workflow for users, the legacy editor also causes a lot of pain on the engineering side. It relies on direct DOM manipulation to render everything in the editor, adding various HTML tags to signify the difference between deleted text, new text and comments. This means engineers on other teams then have to put the article through heavy tag cleanup before it can be published and rendered to the website, a process that is time-consuming and prone to mistakes.

As the newsroom evolves, we envisioned a new story editor that would visually bring the different components of stories inline, so that reporters and editors alike could see exactly what a story would look like before it publishes. Additionally, the new approach would ideally be more intuitive and flexible in its code implementation, avoiding many of the problems caused by the older editor.

With these two goals in mind, my team set out to build this new text editor, which we named Oak. After much research and months of prototyping, we opted to build it on the foundation of ProseMirror, a robust open-source JavaScript toolkit for building rich-text editors. ProseMirror takes a completely different approach than our old text editor did, representing the document using its own non-HTML tree-shaped data structure that describes the structure of the text in terms of paragraphs, headings, lists, links and more.

Unlike the output of our old editor, the output of a text editor built on ProseMirror can ultimately be rendered as a DOM tree, Markdown text or any other number of other formats that can express the concepts it encodes, making it very versatile and solving many of the problems we run into with our legacy text editor.

So how does ProseMirror work, exactly? Let’s jump into the technology behind it.

Everything is a Node

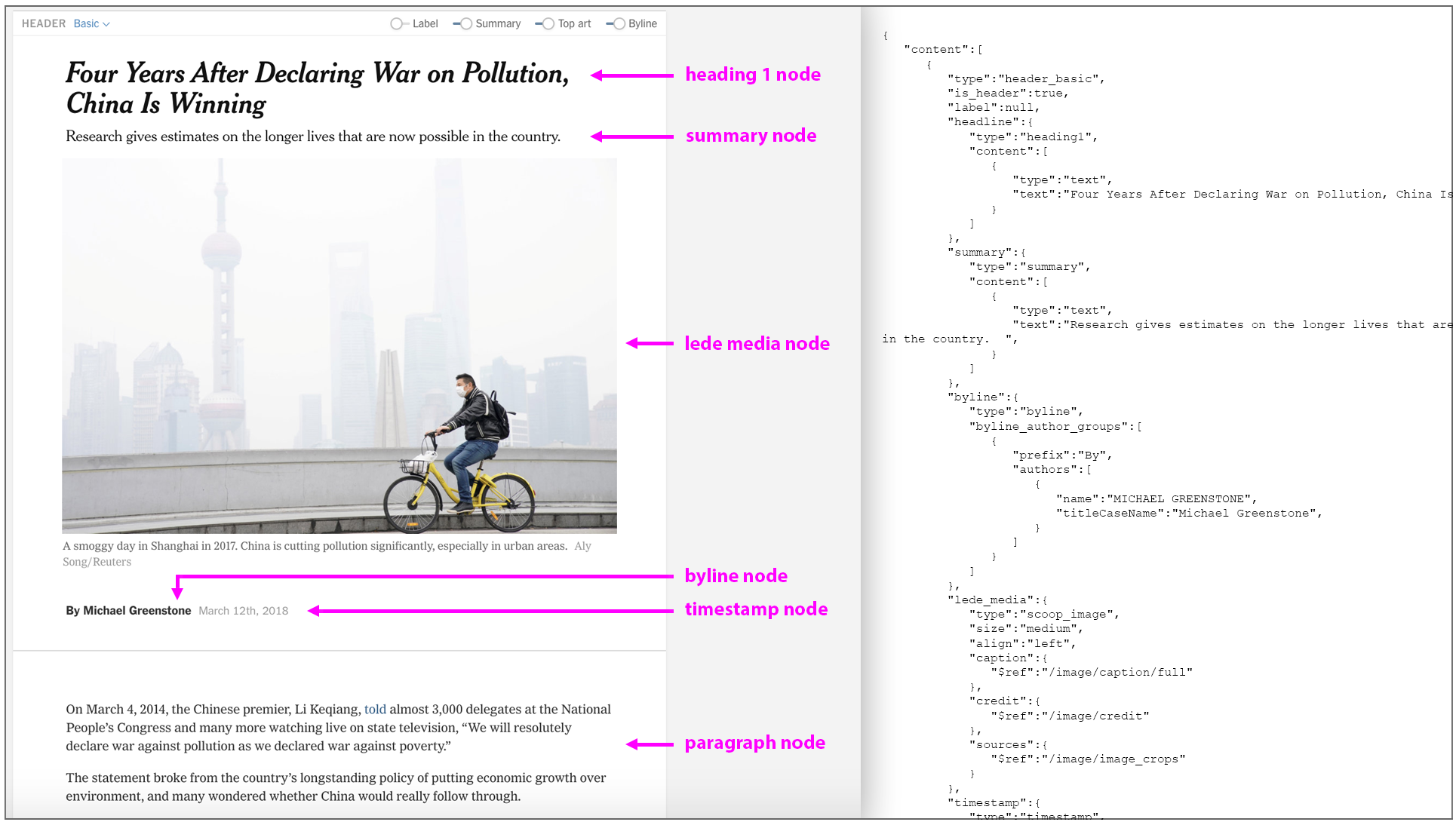

ProseMirror structures its main elements — paragraphs, headings, lists, images, etc. — as nodes. Many nodes can have child nodes — e.g., a heading_basic node can have child nodes including a heading1 node, a byline node, a timestamp node and image nodes. This leads to the tree-like structure I mentioned above.

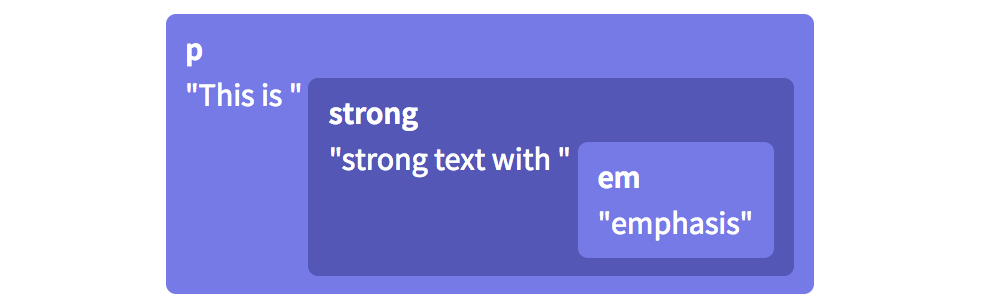

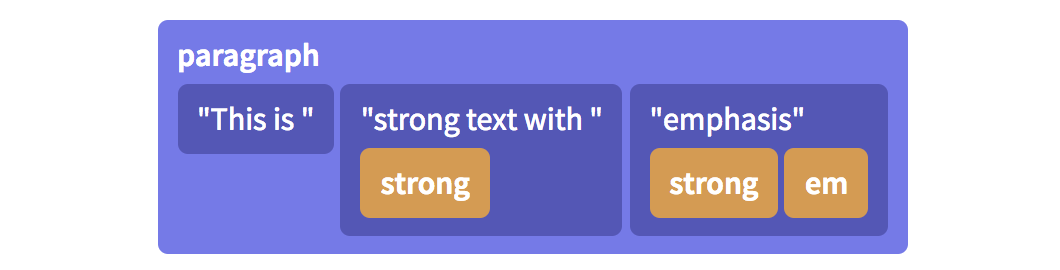

The DOM would codify that sentence as a tree, like this:

In ProseMirror, however, the content of a paragraph is represented as a flat sequence of inline elements, each with its own set of styles:

There’s an advantage to this flat paragraph structure: ProseMirror keeps track of every node in terms of its numerical position. Because ProseMirror recognizes the italicized and bolded word “emphasis” in the example above as its own standalone node, it can represent the node’s position as simple character offsets rather than thinking about it as a location in a tree. The text editor can know, for example, that the word “emphasis” begins at position 63 in the document, which makes it easy to select, find and work with.

All of these nodes — paragraph nodes, heading nodes, image nodes, etc. — have certain features associated with them, including sizes, placeholders and draggability. In the case of some specific nodes like images or videos, they also must contain an ID so that media files can be found in the larger CMS environment. How does Oak know about all of these node features?

To tell Oak what a particular node is like, we create it with a “node spec,” a class that defines those custom behaviors or methods that the text editor needs to understand and properly work with the node. We then define a schema of all the nodes that exist in our editor and where each node is allowed to be placed in the overall document. (We wouldn’t, for example, want users placing embedded tweets inside of the header, so we disallow it in the schema.) In the schema, we list all the nodes that exist in the Oak environment and how they relate to each other.

export function nytBodySchemaSpec() {

const schemaSpec = {

nodes: {

doc: new DocSpec({ content: 'block+', marks: '_' }),

paragraph: new ParagraphSpec({ content: 'inline*', group: 'block', marks: '_' }),

heading1: new Heading1Spec({ content: 'inline*', group: 'block', marks: 'comment' }),

blockquote: new BlockquoteSpec({ content: 'inline*', group: 'block', marks: '_' }),

summary: new SummarySpec({ content: 'inline*', group: 'block', marks: 'comment' }),

header_timestamp: new HeaderTimestampSpec({ group: 'header-child-block', marks: 'comment' }),

...

},

marks:

link: new LinkSpec(),

em: new EmSpec(),

strong: new StrongSpec(),

comment: new CommentMarkSpec(),

},

};

}

Using this list of all the nodes that exist in the Oak environment and how they relate to each other, ProseMirror creates a model of the document at any given time. This model is an object, very similar to the JSON shown next to the example Oak article in the topmost illustration. As the user edits the article, this object is constantly being replaced with a new object that includes the edits, which ensures ProseMirror always knows what the document includes and therefore what to render on the page.

Speaking of which: Once ProseMirror knows how nodes fit together in a document tree, how does it know what those nodes look like or how to actually display them on the page? To map the ProseMirror state to the DOM, every node has a simple toDOM() method out of the box that converts the node to a basic DOM tag — for example, a Paragraph node’s toDOM() method would convert it to a <p> tag, while an Image node’s toDOM() method would convert it to an <img> tag. But because Oak needs customized nodes that do very specific things, our team leverages ProseMirror’s NodeView function to design a custom React component that renders the nodes in specific ways.

(Note: ProseMirror is framework-agnostic, and NodeViews can be created using any front-end framework or none at all; our team has just chosen to use React.)

Keeping track of text styling

If a node is created with a specific visual appearance that ProseMirror gets from its NodeView, how do additional user-added stylings like bold or italics work? That’s what marks are for. You might have noticed them up in the schema code block above.

Following the block where we declare all the nodes in the schema, we declare the types of marks each node is allowed to have. In Oak, we support certain marks for some nodes, and not for others — for instance, we allow italics and hyperlinks in small heading nodes, but neither in large heading nodes. Marks for a given node are then kept in that node’s object in ProseMirror’s state of the current document. We also use marks for our custom comment feature, which I’ll get to a little later in this post.

How do edits work under the hood?

In order to render an accurate version of the document at any given time and also track a version history, it’s critically important that we record virtually everything the user does to change the document — for example, pressing the letter “s” or the enter key, or inserting an image. ProseMirror calls each of these micro-changes a step.

To ensure that all parts of the app are in sync and showing the most recent data, the state of the document is immutable, meaning that updates to the state don’t happen by simply editing the existing data object. Instead, ProseMirror takes the old object, combines it with this new step object and arrives at a brand new state. (For those of you familiar with Flux concepts, this probably feels familiar.)

This flow both encourages cleaner code and also leaves a trail of updates, enabling some of the editor’s most important features, including version comparison. We track these steps and their order in our Redux store, making it easy for the user to roll back or roll forward changes to switch between versions and see the edits that different users have made:

Some of the Cool Features We’ve Built

The ProseMirror library is intentionally modular and extensible, which means it requires heavy customization to do anything at all. This was perfect for us because our goal was to build a text editor to fit the newsroom’s specific requirements. Some of the most interesting features our team has built include:

Track Changes

Our “track changes” feature, shown above, is arguably Oak’s most advanced and important. With newsroom articles involving a complex flow between reporters and their various editors, it’s important to be able to track what changes different users have made to the document and when. This feature relies heavily on the careful tracking of each transaction, storing each one in a database and then rendering them in the document as green text for additions and red strikeout text for deletions.

Custom Headers

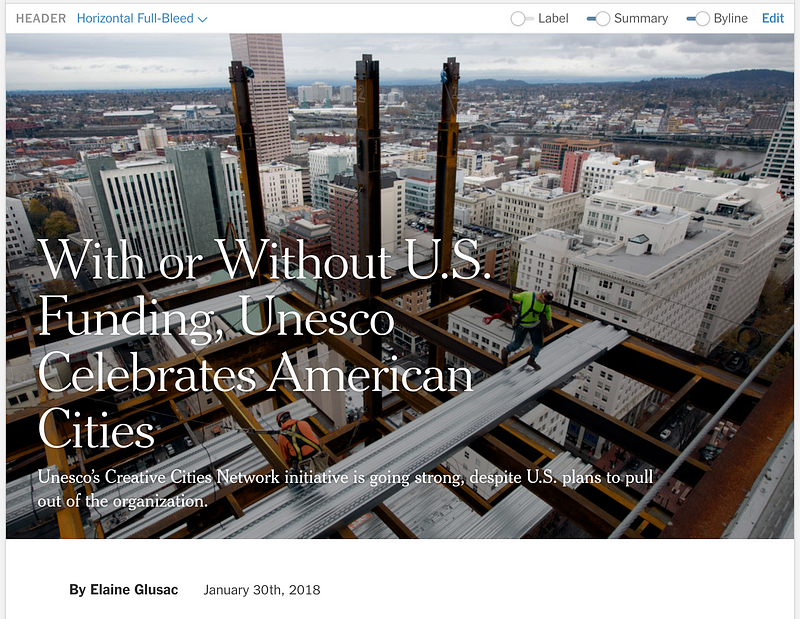

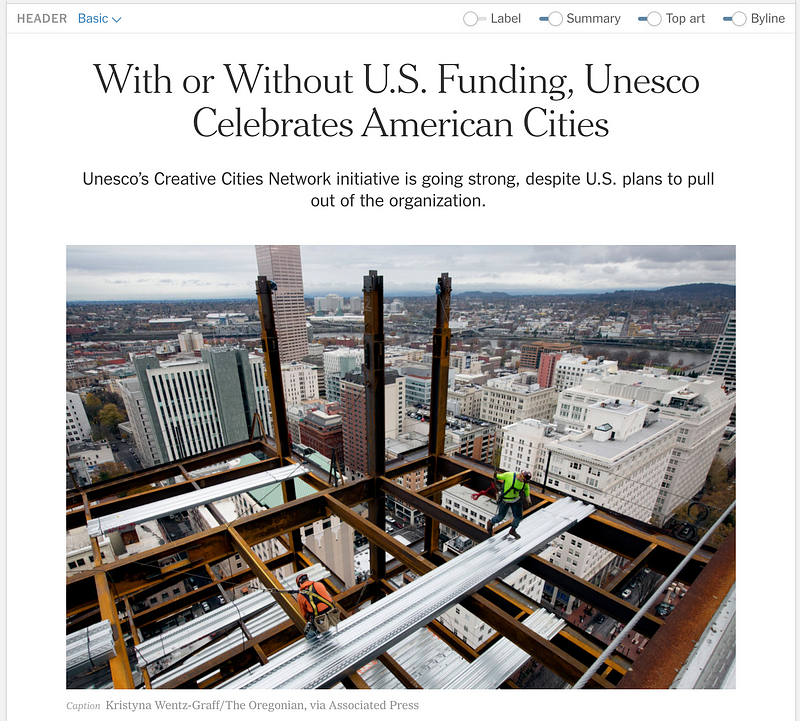

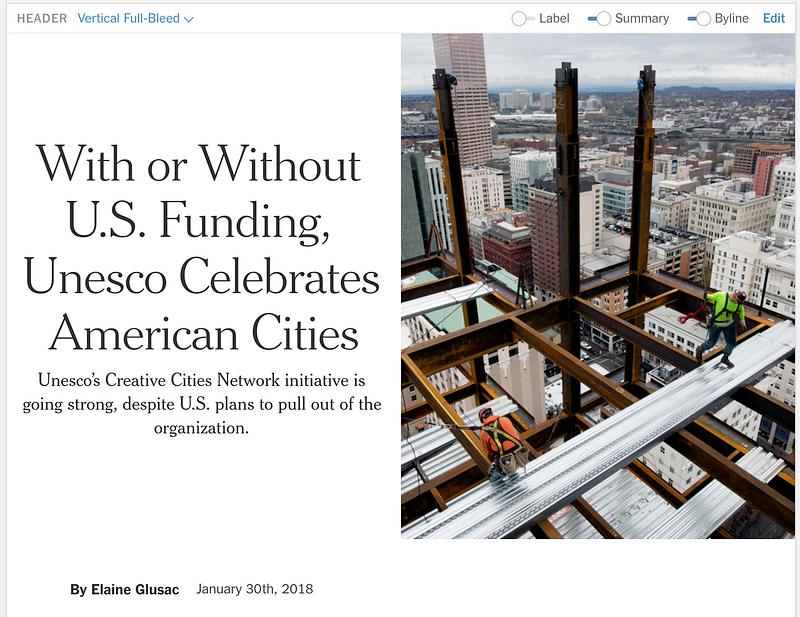

Part of Oak’s purpose is to be a design-focused text editor, giving reporters and editors the ability to present visual journalism in the way that best fits any given story. To this aim, we’ve created custom header nodes including horizontal and vertical full-bleed images. These headers in Oak are each nodes with their own unique NodeViews and schemas that allow them to include bylines, timestamps, images and other nested nodes. For users, they mirror the headers that published articles can have on the reader-facing site, giving reporters and editors as close as possible a representation to what the article will look like when it’s published for the public on the actual New York Times website.

A few of Oak’s header options. From left to right: Basic header, Horizontal full-bleed header, Vertical full-bleed header.

Comments

Comments are an important part of the newsroom workflow — editors need to converse with reporters, asking questions and giving suggestions. In our legacy editor, users were forced to put their comments directly into the document alongside the article text, which often made the article look busy and were easy to miss. For Oak, our team created an intricate ProseMirror plugin that renders comments off to the right. Believe it or not, comments are actually a type of mark under the hood. It’s an annotation on text, like bold, italics or hyperlinks; the difference is just the display style.

In Oak, comments are a type of mark, but they’re displayed on the right side of the relevant text or node.

Oak has come a long way since its conception, and we’re excited to continue building new features for the many newsroom desks that are beginning to make the switch from our legacy editor. We’re planning to begin work soon on a collaborative editing feature that would allow more than one user to edit an article at the same time, which will radically improve the way reporters and editors work together.

Text editors are much more complex than many know. I consider it a privilege to be part of the Oak team, building a tool that, as a writer, I find fascinating and also so important for the functioning of one of the world’s largest and most influential newsrooms. Thank you to my managers, Tessa Ann Taylor and Joe Hart, and my team that’s been working on Oak since well before I arrived: Thomas Rhiel, Jeff Sisson, Will Dunning, Matthew Stake, Matthew Berkowitz, Dylan Nelson, Shilpa Kumar, Shayni Sood and Robinson Deckert. I am lucky to have such amazing teammates in making the Oak magic happen. Thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment