The cherry blossoms are in full bloom. And when I was a wee lass, before the Washington Nationals came to fruition, April also meant that the Baltimore Orioles were kicking off the baseball season at Camden Yards.

This week marked one of my first visits back to D.C. during the month of April since I was an undergrad. Things felt different. My parents live in Florida now. Penn Quarter has completely transformed, as has its neighboring Capitol Hill, where my work brought me for the week. The city has become very expensive.

And despite spending my days in the trenches of the tech industry and the businesses that comprise it, somehow, visiting Washington, D.C. as Congress played host to one of Silicon Valley's highest-profile CEOs felt, in a word, odd.

Over the course of two days, my colleague, HubSpot's Social Campaign Strategy Associate Henry Franco, and I spent no fewer than ten hours sitting in on Mark Zuckerberg's congressional hearings, as he answered questions from Senators on Tuesday and Representatives on Wednesday.

There was a mixed response to these questions and Zuckerberg's answers alike. Were the lawmakers properly prepared for and informed about these events? Was Zuckerberg? And was 10 hours really enough to get to the bottom of the data privacy and other issues the Facebook CEO was invited to Capitol Hill to speak on?

What makes this situation -- Mark Zuckerberg's congressional testimony and the events leading up to it -- so complex is that it cannot be boiled down to a single issue. Instead, it’s comprised of many issues, each of which have many sides. Should Facebook be regulated? Should it stand alone in this regulation? What would that regulation look like? And for all its talk: How likely is it that such federal regulation will actually come into force in the U.S.?

And those are only a few of the questions I have. The irony, of course, is not lost on me that a week of hearings intended to respond to lawmaker inquiry -- as well as the public it represents -- has only led to more questions.

Here's a deeper look at some of the more crucial of them.

Will there be regulation?

As I noted in yesterday's recap of Zuckerberg's House Energy and Commerce Committee hearing, the topic of regulation drew a stark party line on which Representatives fell staunchly one side or the other. Representative Jan Schakowsky of Illinois firmly stated that Facebook's "self-regulation simply does not work." Representative Chris Collins of New York called her remarks "aggressive" and "out of bounds," adding that when he was asked if he agreed with the idea of regulating Facebook, "I said no."

Regulation seems a point of contention among lawmakers, and not just when it comes to Facebook, especially in the context of the European Union's General Data Privacy Regulation (GDPR) coming into force next month. It reflects an era in which consumer demands for data protection are growing, with the latest turn of events concerning Facebook being only one of the more recent examples.

Throughout the hearings -- and in the weeks leading up to them -- Zuckerberg was asked numerous times for his stance on the GDPR, though he hasn't fully spoken to his complete stance on it. In an interview with Reuters, he said he agrees with it "in spirit." In a call with members of the press last week, he remarked, "if we are planning on running the controls for GDPR across the world ... my answer [is] yes." And on Tuesday's Senate hearing, he noted that he believes it "get[s] some things right."

ZUCK: Senator, I'm not opposed to regulation.

Graham: Do you think the Europeans got it right?

ZUCK: I think ... they ... get things right ...

But when it comes to Facebook extending GDPR-like protections to global Facebook users, including those in the U.S., Zuckerberg has given wavering and at times contradictory answers. Rep. Schakowsky pressed him on this yesterday, noting that it sounded as though Zuckerberg's version would be far from "an exact replica" of European regulations.

It reflects a historical corporate resistance to regulation in the U.S., with many consumers long holding that it lags behind the E.U. in terms of transparency and what is disclosed to consumers. (As a non-tech example, throughout most of Europe, food companies are required to label genetically modified products, whereas in the U.S., similar legislation has struggled to pass.)

Which raises the initial question here: Will there be regulation? With the public, along with some lawmakers, calling for increased data protection globally, it leaves us at a watershed moment in the relationship between consumers and the businesses they use.

Rep: Schakowsky: "You have a long list of growth and success, but you also have a long list of apologies," starting with one in 2003. Lists out the chronological apologies. I think she got this list from the @washingtonpost chart published on this earlier this week.

"This is proof to me that self-regulation simply does not work," she says, pointing to the Secure and Protect Americans' Data Act: schakowsky.house.gov/press-releases…

But there's also the ongoing discussion of how well-equipped lawmakers are to regulate a company with the reach and breadth of Facebook's. (At certain points in the hearings, for instance, Zuckerberg was questioned about Facebook's possible monopoly.) As I noted earlier, questions from committee members left the impression that they were either ill-prepared for Zuckerberg's testimony, or simply uninformed about the tech industry as it currently stands.

That was particularly true at Tuesday's hearing, where much of the discourse from Senators suggested a broad lack of understanding of online platforms and where data becomes involved with them.

If that misunderstanding is as widespread throughout Congress as some have suggested, the timing of regulation and the swiftness with which it could be passed comes into question. And it may require further information and testimony -- not just from Zuckerberg and Facebook.

That brings me to another key point.

Why Facebook?

On my way back to Boston after the hearings, a friend texted me to ask how my visit went and what the hearings were like. And then, he made a joke about it.

"I wish there had been this much congressional outrage when Equifax was hacked," he said. "Although, in fairness, Facebook allowed strangers to see my vacation photos and the bands that I like, while Equifax only lost highly sensitive financial information that could ruin people's lives."

Even if my friend's comments were meant to be funny, they did bring up an interesting question: Why Facebook?

Of course, there are some ways to answer that question that are more obvious than others. Facebook experienced the highest-profile weaponization of its platform, after all, for several purposes: alleged election interference, the spread of misinformation and divisive content, and -- as was raised numerous times by Representatives on Wednesday -- ads for opioids and other controlled substances.

Zuckerberg says that if people flag these ads, Facebook will "look at them as fast as we can" and "take [them] down if they violate our policies."

But we also have reason to believe that Facebook isn't alone in the volume and breadth of user data it possesses.

To start, have a look at this lengthy but comprehensive Twitter thread from self-described privacy consultant Dylan Curran, who goes into detail about the depth of information that Google possesses on users.

We also know that this isn't just about data privacy, including where Facebook and the week's hearing are concerned. It's also about the weaponization of online platforms, which are not limited to Facebook, to spread misinformation and divisive content.

Other tech giants have come under fire for falling victim to that. Twitter, for its part, has even submitted a request for proposals to measure the health of its network and how to fix its many problems. And on more than one occasion, Google and YouTube have both been accused of failing to quickly remove false news content during major events.

So, I'll pose the question again: Why Facebook, and Facebook alone?

Zuckerberg listens to opening remarks from House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Greg Walden on April 11, 2018. | Amanda Zantal-Wiener

There may not ever be an answer to the question that satisfies everyone. But as I noted in yesterday's recap, before any firm, sustainable outcomes can result from these ongoing issues, I suspect more hearings will take place. After all, before this week's events, some lawmakers also wanted to include the CEOs of Google and Twitter in the questioning.

On top of that, time constraints played a major role in this week's hearings, with Senators being limited to five minutes of questioning each on Tuesday, and Representatives to four minutes each on Wednesday. For that reason, it may not come as a surprise if Zuckerberg is also asked to appear for an additional round of questioning -- perhaps involuntarily on future occasions.

Furthermore, a Special Counsel investigation into overall election interference is still underway, for which Zuckerberg said in Tuesday's hearing someone from Facebook was questioned. It seems that I'm not the only one who still has questions, and as I wrote yesterday: The testimony, it seems, is far from over.

If Facebook truly puts community before advertising revenue, what will happen?

In his full written testimony for the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Zuckerberg concluded with a sentiment and promise that would be alluded to throughout the hearings:

"My top priority has always been our social mission of connecting people, building community and bringing the world closer together. Advertisers and developers will never take priority over that as long as I’m running Facebook."

Which poses the question: If that's true, and Facebook continues to move away from the "platform before participants" mentality, as HubSpot VP of Marketing Jon Dick put it -- what happens to the businesses who have come to rely on it?

After all, it was something that Zuckerberg repeated throughout the week: Facebook does not sell data. Rather, advertisers build targeted ads on the platform based on the data that Facebook possesses on user behavior and preferences.

That data, Zuckerberg was sure to remind lawmakers, was largely comprised of information that users had to opt-in to providing when they joined the network (such as Page and post Likes) and could not be personally identifiable when used properly.

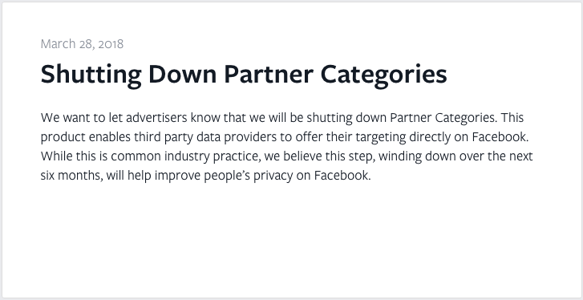

There was also a time when Facebook partnered with other firms, such as Experian and Acxiom, to provide advertisers with supplemental data that could be synthesized in tandem with Facebook's own aforementioned data, helping to match (or target) promoted content to the most relevant audiences. But in the weeks leading up to the hearings, Facebook shuttered that program.

Source: Facebook

For its own part, Zuckerberg has suggested that were it not for this model, Facebook's livelihood could certainly become compromised. In 2017, for instance, advertiser-related income made up 98% of its global revenue -- which many expect to take a hit if the network truly makes good on its promise to de-prioritize advertiser content, or if it continues to limit targeted ad capabilities.

But what didn't come up nearly as much throughout the hearings was the impact that these changes could have on the advertisers themselves -- the good actors who don't weaponize Facebook, but have come to depend on it to build and reach an optimized audience.

That concept actually revisits the topic of regulation, and what it could look like when applied to Facebook. As I already covered, if such regulation does come to fruition, there's a fair chance that it won't only apply to Facebook, but could also extend to the tech industry in general. That could cause a major ripple effect in the way all online companies conduct business, and the way consumers and advertisers alike can use them.

Even if the implications of regulation are massively widespread, it might not be an entirely negative thing. As Zuckerberg and lawmakers were both sure to remind us this week, the issues at-hand are fundamentally about trust. And further restrictions -- or at least rules around how Facebook can manage and allow advertising -- could potentially lead to a larger degree of consumer trust on how, exactly, advertisers reach them.

In other words -- Facebook moving away from the "platform before participants" mentality might not be entirely bad for advertisers, many of whom are all too familiar with pressure to grow which leads to equal pressure and temptation to use short-cuts or overly aggressive tactics for reaching customers.

The better alternative, perhaps, comes in the form of promoted content that is at least more personalized, which Zuckerberg spoke to this week. Facebook users would prefer an ad that's relevant, he maintained throughout the hearings, than non-ad content that isn't relevant at all.

Zuckerberg adds: "It would impact our revenue somewhat, too," but he doesn't seem to want to dwell on that

That profitability aspect, Mallikarjunan said, will always be core to the degree of Facebook's self-regulation. "Until Facebook designs a system where spamming is less profitable than creating a good experience for users -- what search engines and e-mail inboxes have done -- this will continue to be an issue."

But, at this point, much of this is a hypothesis. We still don't know what regulation would look like, if it even came to be, and we don't know how many additional changes Facebook is going to make to the way it collects, uses, or retains this data -- or to the way advertisers can best leverage the platform.

We don't know if this visit was his last to Capitol Hill -- though I think not. And according to the Washington Post, his presence has once again been requested by European lawmakers, after he previously declined to testify before United Kingdom Members of Parliament.

We still don't know what leaders at Google, YouTube, and Twitter have to say -- or if they'll be asked by lawmakers for their input.

And, we still don't know who else will be held accountable, and to what degree, as these issues continue to be discussed -- like Kogan, Cambridge Analytica, or Eunoia, to name a few.

Most of all -- we don't know if we will ever come to learn more about these lingering questions.

But if we do -- I'll let you know.